Moving from orchestration to choregraphy - Part 1

Over the last decade, Michelin went from a big mainframe monolith to a choreography of micro services streaming business events to support its core business processes: the distribution of tires from our plants to our warehouses. At stake: our ability to deliver our tires to our customers on time and as you can imagine it's quite important to us.

We wrote this series of articles to share that journey with you. This first part will try to explain where we came from, why we first adopted an orchestrator style and finally moved to a choregraphy one. The second one will focus on the implementation of our new micro-services based choregraphy while the third will share what we learned along the way. We hope you'll enjoy this trip.

From monolith to orchestration first

A decade ago, most of this value chain was supported by our mainframe systems and over time it became difficult to maintain not even mentioning the over increasing running costs. We decided to revisite our architecture to decompose this big monolith with several COTS (Commercial Of The Shelf) to support the main services:

- a DRP system to compute the deployment plan of our tires from plants to warehouses

- a Transportation Management System to optimize our logistic

- a Warehouse Management System to manage our inventories

An industrial group like Michelin induces some business complexity. Depending on the region you are in, the type of customers (retails or original equipment), the import / export opportunities, you end up with dozen of business processes to support these kind of flows. And eight years ago, business processes often rhymed with an orchestrator engine to implement what we call a Business Process Management solution. That's what we did with the introduction of a central orchestrator to pilot these COTS and ensure the proper execution of our processes. This first move clearly helped in our strategy to decompose of big mainframe monolith.

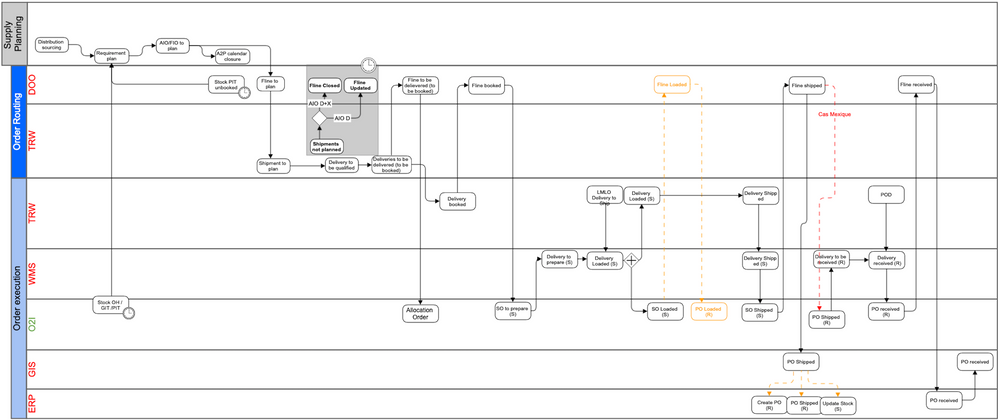

The below figure illustrates one of the 17 business processes we implemented. It's described using the BPMN standard. The swim lanes represent the main functions contributing to the end to end process. Swimlanes can either be supported by one or more applications. For instance TRW and DOO applications support the order routing area. You can see below the different tasks involved in this process and the orchestrator is represented by the DOO sub swimlane. Visually, all other swimlanes are either sending messages to it or receiving one from it placing DOO as the heart.

This orchestrator went live and it was not easy as you can imagine mainly because of its central positionning and the numerous applications involved. But after several years of effort and a progressive roll out, ==ten billions== euros of Michelin turn over are flowing through this orchestrator.

But over time, new difficulties arised directly linked to this BPM style. Among other things, one finds:

- the introduction of a single point of failure. By definition, such orchestrator is a central piece of your architecture and as such any time it faced a failure, there was a direct impact on our business performance. At the end the day, our customers were directly impacted by those failures.

- BPM engines are aging and as many aging solutions (like ERPs), we could not benefits from the latest innovations bring by the IT industry. Most (if not all) software vendors selling BPM engines are stucked in the application server world and as such it was not possible for them to deliver near zero downtime upgrades, automations & scalability to their customers.

- As our orchestrator was introduced to decompose our monoliths, we used it as much as we could to limite the impact of our legacy systems. Indeed our mainframe applications were so costly to change (and that's still the case today) that we prefered to implement more logic in our orchestrator. It was fine at the beginning, but over time, the complexity of this logic became so high that the maintenance of our orchestrator became as difficult as our legacies.

- Something else unexptected happened: the team building our orchestrator loosed the knowledge of its own solution. It did not happen over night of course. In many big organisations, the project mode prevails and that's the case at Michelin. With one project succeeding to another, the natural attrition was at work. And if in the mean time, team members were replaced slowly but surely, you end up with people that never touched some business process because the project they were working on was impacted a different area. So over time, we can say we did not master anymore our orchestrator.

Then from orchestration to choreography

It was the right time to get rid of our orchestrator and move on. And we did it but it was not an easy journey.

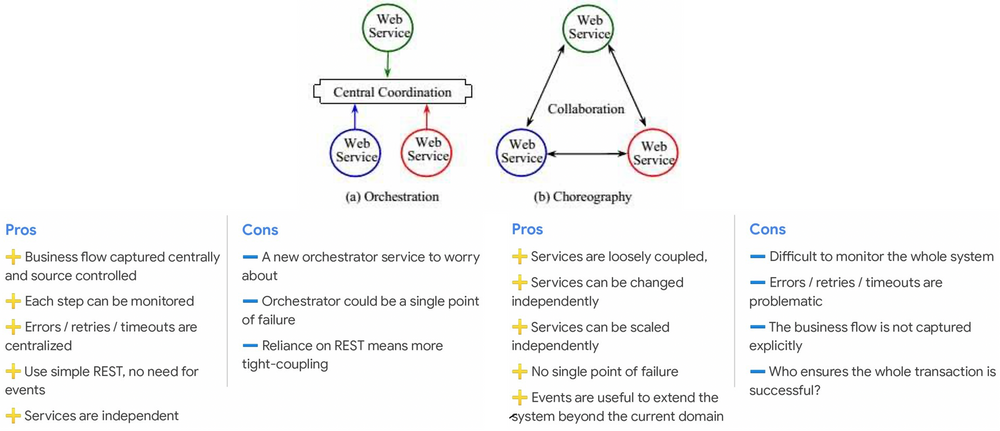

We had to choose how we would replace our orchestrator. So we started to explain we wanted to move away from the orchestration approach to adopt a choregraphy of business events instead. The below figure illustrates the differences between these two approaches. And of course there are pros and cons for both of them as you can see.

The problem with such "orchestration or choregraphy, that's the question" debate is that it can quickly become what I call the realm of opinions. If you're asking a process believer or a BPM engine vendor, he will answer "yes of course, you need an orchestrator engine". If you're asking a fan of event driven architecture, he'll reply "choregraphy is the new heaven, go for it full speed". There are few people thoughts that are a bit more balanced. Bernd Rücker is one of them. He's the CTO of the Camunda company and as such we could expect a big BPM believer. But he understood two important things:

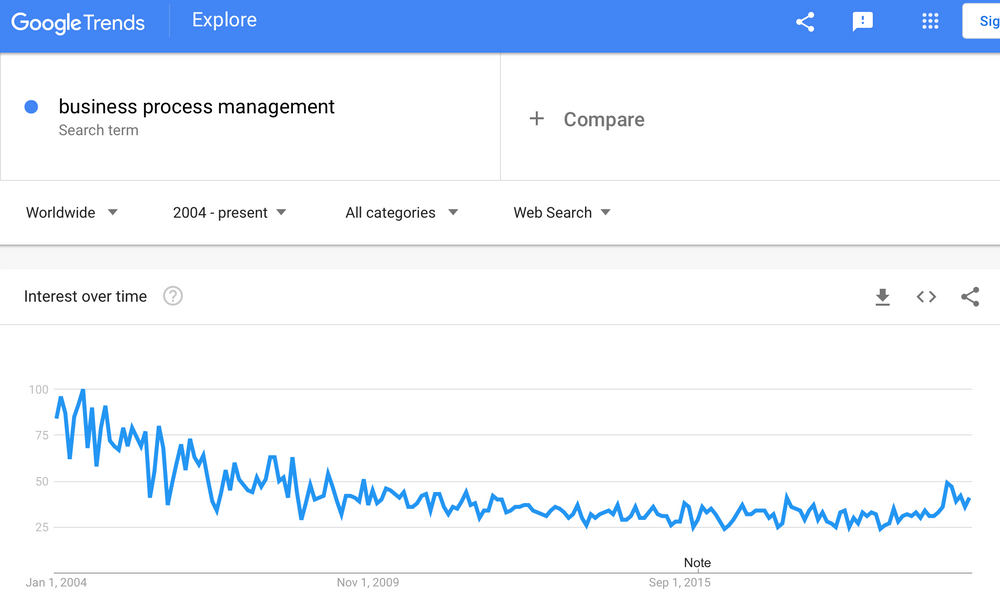

1. Big monolithic BPM engines to orchestrate end to end processes belongs to the past. And it's not only a technical believe: modern companies must get rid of end to end processes to increase their agility. So this market is doomed basically. I often used the Google trends tool and if you use it with Business Process Management term, you'll end up with the figure below:

2. Event driven architecture and choregraphy improve the modularity of your information system but they are hard. Providing monitoring capabilities and is some cases a workflow engine for very complex sub-areas could make sense.

Bernd was really inspirational for us at Michelin. The fact that our processes were already relying on a set of business events like truck loaded, truck shipped, delivery booked, goods received ... made our life a bit easier. It was easy to explain that instead of having a piece of software executing our processes (with many inbound and outbound events), we could replace it with a set of smaller pieces that would subscribe to some events and produce others. The advantages of this approach are multiple and are all linked to the fact that choregraphy promotes modularity. And we love modularity because it helps to create smaller pieces that can evolved independently and scale differently. And because the sequence of events is not hard coded, it means you can add into it a step without impacting (or with small impacts to be honest) upstream and downstream systems. Isn't it beautiful? Why would we not go for it?

We were convinced of course. But many were not. And even if we could describe the pains inherently attached to a central orchestrator, there were valid concerns with the choregraphy approach: we had to convince! Over the years solid believes were constructed:

1. You have to understand that it's not because we want to decomission our orchestrator that the need to support our business processes disappeared. Many people were convinced we needed a central piece of software to ensure the right execution of these business processes. And below the surface, one founds the observability of our system.

2. There were also people deeply believing that the different systems contributing to these processes were not able to decide by themselves what to do: this intelligence had to be centralized somewhere. Otherwise, the integrity of the system would be jeopardized.

So let's try to tackle those believes !

With a BPM engine, the monitoring of processes execution comes by design. If you remove the engine, so does the monitoring.

First we had to explain that end to end monitoring was not a "real" need expressed by our end users. They wanted to see what was happening on the transport area or the supply chain one, but nobody was asking for something end to end. So the problem became simple to solve: how to observe part of the systems? With a choregraphy of events, observality is absolutely key to understand what is happening and trouble shoot problems. We ended up with a set of simple rules:

- each and every piece contributing to the choregraphy shall publish incoming events and produces ones

- for areas where we needed to provide business monitoring we sourced a specific solution that would consume the observables and produce the appropriate dashboards

Then, we had to address the fear around the maintainability of the overall system. Even if we demonstrated that this problem was already there with an orchestrator, there was a believe that a choregraphy model would make that problem bigger. Our first proposal was to give back the ownership of some part of these processes to the operational systems themselves. Who is better positionned to maintain the business logic on logistic transport than the team managing the product optimizing it? This proposal was not well received mainly because the believe that we needed a central team to manage these rules was too anchored. So, we decided to re-create a central team that will implement this whole choregraphy but that was a compromise. We are still convinced that this team is an organizational coupling point and in a near future, we'll need to remove it to avoid a bottleneck in the delivery.

To win the final decision, we decided to execute a proof of concept with the technology stack we recommended to demonstrate several things:

- the effort to re-develop a process is not that huge

- the proposed technology stack can scale and meet our availability needs

- we could propose a monitoring solution to observe our choregraphy

The POC was sucessfully done and the decision was taken to proceed. You're probably asking yourself: "what is this technology stack they used?" If you want to know about it, stay tuned and wait for the second part of this serie ;)